From The Guardian

Outside Norwich, in a refrigerated cupboard in the basement of the John Innes Centre, racks of glass tubes filled with bright green shoots have been arranged in neat, carefully labelled layers. They look like salad pots at a fast-food outlet.

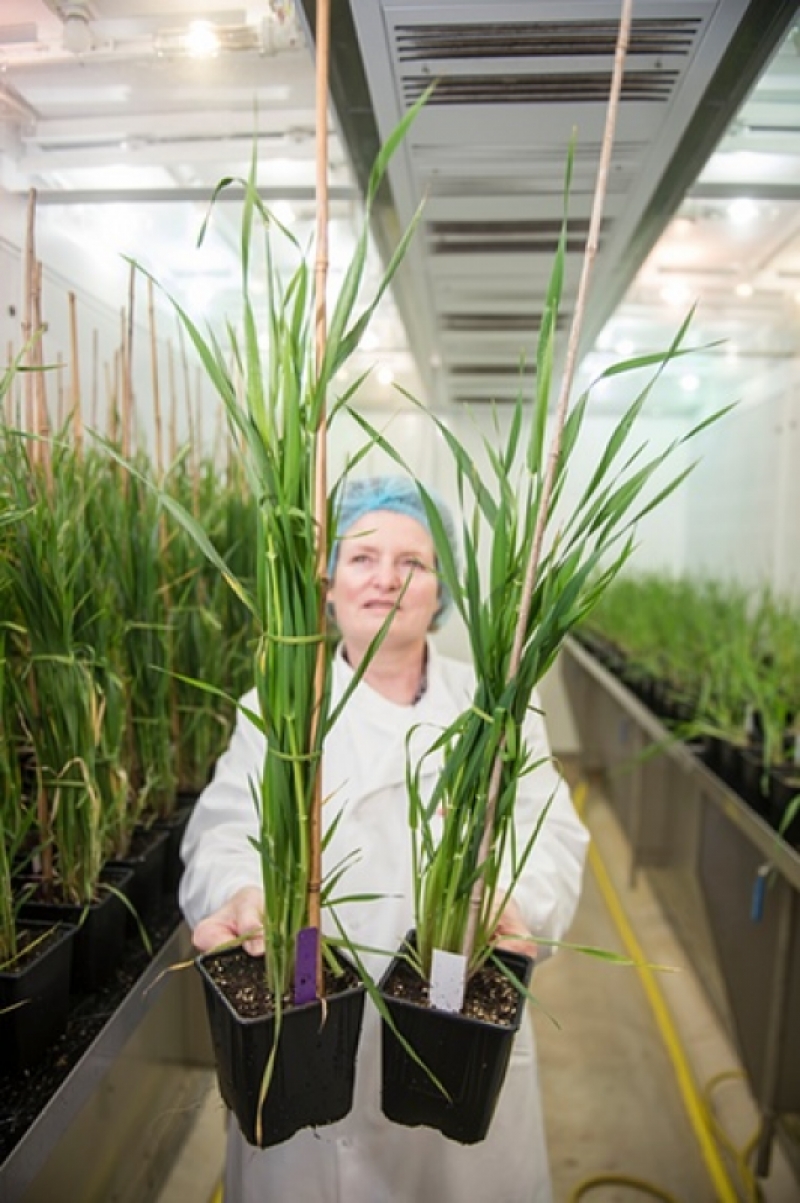

These young barley plants are special, however, and not for sale. They have been grown from seeds whose DNA has been subtly altered by a technique known as gene editing and they hold dramatic promise, scientists at the crop research centre believe. Their makeup is being tweaked in an attempt to create a strain of barley that would make its own ammonium fertiliser from nitrogen in the soil: this would be a major boost for farmers who lack rich soil or money to buy artificial fertilisers.

The art and science of gene – or genome – editing is making waves. Last week it generated headlines when researchers were given the go-ahead to use the technique to alter human embryos in a project aimed at better understanding the causes of miscarriages. Now it is set to have an equally revolutionary impact on agriculture – though for gene-edited crops, the science faces a serious obstacle. In a few weeks, European commission regulators are set to publish a report that will decide whether gene-edited crops should be considered to be genetically modified organisms.

If the commission report backs such a verdict, the stringent EU legislation and complex regulations that have almost completely blocked the growing of GM (genetically modified) crops in Europe would be extended to those created through gene-editing – despite the relative simplicity of the technique and the vast potential it holds.

“It would be a real step backwards,” said Professor Wendy Harwood, leader of the gene-edited barley research project. “It would turn projects that cost a few thousand pounds into ones that would require millions of pounds of funding to fulfil the requirements of the complex EU bureaucracy that is used to regulate GM crop growing in Europe. Only big biotechnology companies would be able to afford to make gene-edited crops.”

It’s a worrying prospect for scientists, and many now fear that the commission ruling will go against them. “I am very pessimistic,” said Professor Michael Bevan, another John Innes researcher. “The EU food standards agency has already been making pronouncements that they are going to class anything that is ‘not natural’ as GM. If they go ahead with such a decision, they will cut off many approaches for creating new foods and crops.”

Gene-editing techniques work like the find-and-replace function on a word processor. First, they locate a gene to be edited, then they make the necessary change to it, either by deleting or repairing it or, in some cases, by inserting a new gene from another species. The technology has made genetic modification a dramatically simpler process to operate and is transforming medicine. But the technology also has considerable agricultural potential. Instead of inserting a completely new gene from another organism into a plant’s chromosomes – genetic modification – the new technique of gene-editing usually only involves fiddling with the crop’s existing DNA.

“You can tell if a crop has been genetically modified, but it is impossible to tell if a plant has been subject to gene editing,” added Harwood. “It is closer to old-fashioned breeding techniques than it is to genetic modification technology.”

The green movement disagrees. It views gene editing as a technique that is hardly different from the genetic engineering techniques used to make GM crops. Hence its support for the inclusion of gene-edited crops within the EU’s GM regulatory framework.

“Gene editing changes the genetic code using material from outside the target organism,” said Franziska Achterberger of Greenpeace. “Much like older genetic modification techniques, it also entails numerous risks and uncertainties. The engineering process is not well-understood and can result in unexpected and unpredictable effects on the environment and human and animal health.”

But most scientists argue that if regulations covering GM crops are extended to those created by gene editing – a technique that has emerged only in the past two or three years – the impact would be profound and harmful. Stringent EU rules and the efforts of green activists have ensured GM crops have become, in Europe, as rare as sunflowers in the desert. Only one genetically modified strain is now grown commercially within the whole of the EU. This is Bt maize, engineered to produce toxins derived from the soil bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt). This poison kills the European corn borer worm, a substantial maize pest, and so the GM version of the crop needs less insecticide than standard, non-GM strains.

This dearth of GM crops has not stopped genetically modified foods from appearing in the UK, however. Much soya-based animal feed imported into the UK is genetically modified. As a result, most non-organic pork and chicken meat in our supermarkets comes from animals that have been reared on imported GM feed.

Nor have UK scientists given up trying to create new GM crops. Potatoes that can resist blight and aphid-resistant wheat have been developed and field trials launched, sometimes sparking violent protest.

Harwood’s trial field of GM barley was destroyed by protesters several years ago. “A year’s work was ruined in a few minutes,” she recalled.

Now Harwood has moved on to use gene editing and is working on a project, backed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, to create cereal crops that make their own nitrogen fertilisers. “Nitrogen fixing is complex but we are uncovering how it works by switching off individual barley genes using gene editing and so working out a pathway that could allow cereals to make their own ammonium fertiliser. The point is that gene editing makes this a very simple process – and a very promising one.”

Other gene-editing work at the John Innes Centre includes research by Professor Cathie Martin, who is working on creating strains of beetroot that could produce L-Dopa, a drug used to treat Parkinson’s disease. “Beetroot make L-Dopa, but other genes then turn this compound into dyes,” said Martin. “It is the process by which the vegetable gets its deep purple colour.

“However, we are working on ways to gene edit beetroot to turn off those pathways and so let the L-Dopa accumulate inside it. In this way, we would make a white beetroot filled with drugs to treat Parkinson’s disease. For poorer countries this would be a particularly important, cheap source of a drug that might be too expensive to buy.”

The crucial point, adds Martin, is that the creation of an L-Dopa beetroot is possible by standard breeding techniques, but would take far longer than it would using gene editing, provided this were not entangled in complex EU regulations. “The two techniques produce indistinguishable results, but one – gene editing – is much quicker to implement,” she added.

Scientists acknowledge that in some cases – when it is used to insert a completely new gene – gene editing could be seen as genetic modification. But in many cases it involves merely deleting a few bases of DNA from a plant’s chromosome. “That type of gene editing should not be covered by GMO regulations,” said Professor Huw Jones of Aberystwyth University. “A blanket imposition of GMO regulations for gene editing would simply be wrong.”

The green movement is unconvinced. “The various gene-editing technologies are still GM, and we are clear they fall within the definition of GM in existing EU law,” said Lord Melchett, policy director of the Soil Association and one of the key players in the UK organic food industry. “Gene editing carries with it the same potential for unforeseeable disruption of the genome as other GM technology, meaning that these interventions into the genome can lead to unpredictable and unexpected impacts on the performance and safety of crops.”

Whatever the European commission decides will trigger considerable controversy. Most analysts expect either a company or an NGO to take legal action over the issue – which will end up being resolved at the European court of justice. The long struggle to legitimise the use of modern genetics on the farm goes on.

Gene editing: should Britain embrace it?

Yes

Huw Jones, professor of translational genomics, Aberystwyth University

Gene-editing tools such as Crispr have huge potential for research and for practical applications in healthcare and agriculture. This promise will be realised only if the European commission grasps the nettle and sets out a regulatory framework that is logical, proportionate to the risks and has broad support from the public, researchers and the plant-breeding industry.

Basic gene editing makes mutations that are indistinguishable from those found in conventional breeding so it makes no sense to call these GMOs. Better to regulate them simply as “novel foods”. The commission has a unique opportunity to democratise biotechnology. It is currently dominated by a few multinational companies which, understandably, concentrate on profitable traits in the major global crops.

Reducing overly burdensome costs and streamlining regulation for gene-edited plants with no foreign DNA would not only be logical, but allow smaller plant breeders and research organisations to use these benign methods for public-good breeding projects in locally important crops, and focus on less-profitable traits for sustainable agriculture and nutritional quality.

We now have the editing tools to translate the wealth of available genomics information into safe and nutritious food. I urge the commission to stimulate democratic innovation in plant breeding by excluding simple gene editing from current GMO legislation.

No

Liz O’Neill, Director of GM Freeze

If this group of genetic engineering techniques escape classification as GM, they could be completely unregulated. The crops they produce could find their way into our fields and on to our plates without environmental or food safety risk assessments. They would not be traceable and, without labelling, consumers would have no way to identify and avoid them should they wish to do so.

We hear a lot about the precision of the new methods, but they are all vulnerable to off-target effects of one kind or another and precision isn’t the same as predictability. We know that genes interact with each other in complex ways. Changing the way that one gene is expressed can have an effect on a completely different part of the genome. So even if one is successful in altering DNA in exactly the way intended, unexpected effects can still occur.

These techniques have no history of safe use and, because genetic pollution is almost impossible to “mop up”, any problems they do cause will be incredibly difficult to put right.

GM Freeze wants our food to be produced responsibly, fairly and sustainably, and allowing these techniques to slip through the regulatory safety net on a legal technicality would do the exact opposite.